In the large houses of planters and the rich merchants of Port-of-Spain, Cook sometimes lived on the premises in a detached row of rooms in the backyard which also accommodated other members of the army of servants necessary for the functioning of a gentrified home. Alternatively, Cook lived in one of the poor tenements of barrack yards of east Port-of-Spain, especially if she had children to care for as sometimes Cook was a single mother. In the latter instance, life was one of hard work literally from dawn till dusk. A cook in a “big house” would have to take up duty at six, for at seven, the bell of the clock at the Royal Gaol on Frederick Street would toll forth and like an army, cooks from the fine homes in St Clair and around the Savannah would begin trooping down to the old Eastern Market on Charlotte Street to make their daily purchases, since in the days before widespread refrigeration, most food had to be consumed fresh. As a person of importance in a gentrified household, Cook was often dressed in a vivid Martiniquan headkerchief which, depending on the position of the knot, would announce her status as a married, single or courting woman. Equally picturesque would be the flowing skirts and flawlessly white bodices they wore as they sallied forth with empty baskets on each arm. Before 9 am, the cooks would come trooping back up from market with their baskets filled. One containing greens would be on their arms and behind them would be trailing a ragged Indian porter carrying another heavier basket holding fresh beef, oxtail to be boiled into stock, ground provisions, and sometimes fish. Depending on the type of mistress Cook served, the purchases would have to be spread out in the kitchen for Missus to poke, prod and criticise, giving the latter a sense of having done her domestic duty. After the ordeal of inspection, which would sometimes involve nagging and condemnation (sometimes accusations of mishandling household monies), Cook was free to unleash her creative juices. Assisted by a boy who lit the coalpots and a scullion who prepared the meat and vegetables for the pot (a sous-chef by modern standards), Cook would have a couple hours to serve up a three-or four-course meal to the household (luncheon was called “breakfast” in those days) before beginning preparations for dinner. Cook’s day ended at 8 pm, but she was queen of the kitchen and would benefit from macafouchette, or excess food, and sometimes clothing, which would be taken home to her own family or distributed among favourites from the cotillion of servants in the great houses of yesteryear. Fast food marketing has destroyed many of these indigenous cuisines brought from their homeland of Africa and polished to perfection in the Caribbean space. Sweets were derived from the molasses of the cane (toolum), chili-bibi; ground corn mixed with brown sugar. Guava cheese, coconut bake, coo coo, yam, ochoo sauces, roast plantain, chip chip water, pone. The sharks (American fast food), swallowed the sardines (the queens of the kitchen). Let us revisit the fact that cultural identity is deeply rooted in the foods of the natives. Jamaica is famous internationally for the jerk chicken. The bene ball is vanishing from the landscape of Tobago. Angelo’s (VIrtual Museum of T&T) writing is very relevant in relation to the dwindling foreign exchange market. Was he prophetic about cutting down on acquired foreign taste and cherishing what is clearly our own? Food for thought. Source: The Guardian, March 11, 2017.

0 Comments

Angostura bitters. You’ve definitely seen it: that tiny little bottle with the big white label and the bright yellow cap. It’s an indispensable bar fixture almost as common as ice cubes (so make sure you know how to pronounce it). What is this stuff, exactly? How has it set up camp in pretty much every bar you’ve ever been to? Why should you care? Let’s start at the beginning. SCIENCE, WAR AND A FAMILY BUSINESS The inventor of this tiny tincture is a fellow named Johann Gottlieb Benjamin Siegert, so you know it’s serious. J.G.B. was a medic in the Prussian army, and fought against Napoleon (no big deal). He then went on to become Surgeon General for Simón Bolívar, and was stationed in a little town in Venezuela called Angostura. Siegert became fascinated with the herbs and plants in the area. He experimented with different blends and mixtures to create a bitter medicine to boost the health of the troops. When Bolívar finally moved on to fight across Latin America, Siegert stuck around Angostura and kept working on his recipe. It was years later, when his sons started helping him on the business side of things, that everything changed. They moved operations to Trinidad, sold cases of their bitters to international royalty, and hired a sugar technologist – yes, you read that correctly. To this day, The House of Angostura bottles up bitters for the world to enjoy, using the same recipe Siegert came up with back in 1824. A recipe shrouded in mystique. WANT THE RECIPE? GOOD LUCK WITH THAT. Production of Angostura is kind of cloak-and-dagger. It’s speculated that the recipe contains over 40 ingredients, but only five people on the planet know the formula. They’ve made a pact to never fly on a plane together — or to even eat in the same restaurant. That’s commitment. Raw ingredients are first collected in a facility in England, where they’re separately and discreetly bagged. Then they’re shipped to the island of Trinidad, where everything slips quietly through customs without inspection. It’s all part of a deal the Siegert family made long ago. Once the packages reach headquarters, they’re collected in The Sanctuary, an exclusive upper chamber. That’s where the five secret experts grind and blend the herbs and spices. Next, the base mixture drops, as if from heaven, down into carts on the first floor, where other workers take over. Everything is infused with a high-proof spirit in giant percolator tanks. The resulting distillate is combined with brown sugar and coloring, then diluted to 44.7% alcohol. After that, the treasured bitters are ready to emerge from the shadows of secrecy and depart to the cocktail bars of the world. WHAT’S WITH THAT LABEL? Next, of course, comes bottling, packaging and distribution. And the quirkiness continues. Bottles of Angostura are well-known for the unusual label, which sticks up around the neck like a cone of shame.

The story of the label seems to go something like this: the Siegert brothers were entering a competition. One brother rushed off to get bottles, the other to create labels, but they kind of failed to sync up on the details—so the label was too tall. Without any time to correct it, they headed off to the competition with what they had. Well, they lost. Afterwards, however, one of the judges pulled them aside and said they should keep it as their signature packaging. They took the advice, and it’s been that way ever since. COCKTAILS WOULDN’T BE THE SAME WITHOUT IT. When it comes to cocktails, Angostura is synonymous with several classics. There’s the Old Fashioned, the Manhattan and the Daiquiri, plus a slew of Tiki drinks. Each one only uses a couple dashes of Angostura, but now bartenders are playing with recipes that use much heftier portions. The Angostura Sour holds an incredible 1 1/2 ounces of its namesake bitters. That burly serving gets shaken up with lime juice, sugar and an egg white, which means Angostura is the only boozy ingredient in the mix. This recipe has been around a while, but recently another contender has caused quite a stir, the bracing Trinidad Sour. The Trinidad Sour also contains a whopping 1 1/2 ounces of Angostura. Blended with orgeat, lemon and a touch of rye, this is a varsity-level drink that bartenders admire. In fact, it’s become quite popular, which is why you’ll see barkeeps prying the drip caps off of Angostura bottles, allowing for a steady pour. In 2014, Angostura released a new item to celebrate its 190th year: Amaro di Angostura. The blenders in Trinidad have used their famous flavor profile to create an Italian-style digestif. They suggest using it in the Amora Amaro, a lime-laden cocktail with 1 1/2 ounces of the new amaro, plus an additional 3/4 of an ounce of the bitters. Prepare yourself, friends. BEYOND THE BAR Considering Angostura’s origins, it’s no surprise that there are a lot of other uses for it besides dressing up your whiskey. Siegert created it to alleviate digestive problems and battle Venezuelan parasites. It makes sense, then, that people still take it to calm an unsettled stomach. Similarly, it’s known to tame the acidity of citrus, which is probably why it works so well in the sour recipes above. Angostura can add depth and complexity to everything from stews to seafood to sauerkraut. On the sweeter side, it pushes pies to a whole new spiced-up level, and would probably be pretty interesting in something like a root beer float (or a cocktail that just tastes like one). You don’t have to consume Angostura to make good use of it, though. The wooden fixtures in Seattle’s Canon Bar are all stained with Angostura, an aesthetic feat that must have required a massive supply of those little bitter bottles. Some even say that if you rub Angostura on your skin, it makes an excellent mosquito repellent. Give it a shot? Siegert would, no doubt, be proud. Source: Vinepair  ROYALS ON HORSEBACK: A watercolour depicting the visit by Prince George and Prince Albert to the West Indies in 1880.  There was an unlikely moment in Trinidad's 19th century history when an old African man born before Emancipation and an Indian woman who came to replace him in the fields caught the eye of the future King of England. It happened on an unnamed street in San Fernando the morning of January 30, 1880. Prince George was travelling through the town on his way to check out the Ste Madeleine sugar works that helped fund his family's kingdom when, he says, these two peasants chased after him. They would hand the Prince some treasured possessions, — a silver bangle and a “knobbed stick”, and his entourage stowed away the items. It would later be recorded that the old man's stick, having travelled around the world on His Majesty's ship, was presented to the Queen and kept at her favourite castle in England...forevermore. At least that's the story as told by Prince George in his travelogue before he became King. Whether there is truth to it, well, we decided to find out. It meant searching through 100-year-old inventories, digging up some old photographs, and making contact with those in charge of archiving the thousands of things the Monarchy had been gifted, stolen or plundered from its colonies over the years. And when that search attempt was exhausted, we made the trip over to the United Kingdom's Isle of Wight in search of – a stick. The future King George V, and his brother Prince Albert. Here's what we discovered: In 1877, the two grandsons of Great Britain's Queen Victoria joined the Royal Navy as cadets. Two years later, dad decided it was time for his boys Prince Albert Victor and Prince George to push off on a cruise to see the world, learn the art of seamanship, visit the colonies and consider the might of a British Empire that one of them would later rule over. So as midshipmen, and against the wishes of the Cabinet and their grandmother worried they would drown in a sinking, the Monarchy's future set off on the HMS Bacchante, and spent three years globe-trotting. Among the first places to be visited was the British West Indies, where the brothers, 15 and 17 years old at the time, did us the eternal favour of taking careful and copious notes of their travels around Trinidad and elsewhere. The diary entries would later be compiled by their tutor, Rev John Dalton, in two volumes titled The Cruise of the HMS Bacchante 1879-1882. And in these pages, we get a description, albeit through the eyes and experiences of the pampered, of the island's people and places so many years ago. And while much has changed since that visit, it looks like some had been shamelessly chasing after celebrity even then. Everywhere the princes went — by horse, train, tram, carriage, steam ship — their subjects were sure to follow. The princes wrote: All the negroes and coolies of the villages on the road had hung out flags and made arches of crotons, bamboos and hibiscus (a trumpet-shaped crimson flower), and stepped out in twos or threes to offer oranges or other trifles to us both as we rode along. But it's their trip to San Fernando, arriving by boat after a lime in La Brea, that appeared to have stirred a particularly raucous crowd of town and country folk, who lined the road as their royal highnesses were carried along by horse-drawn carriage, to catch a tram to the Ste Madeleine sugar works and then on to the place that would come to be known as Princes Town. There are no known images of the ordinary folk. The royal photographer apparently liked to takes photos of landscape and buildings. But the princes would record this January visit thusly: “Left the ship at 9.30 a.m. in the Arthur (Turnbull's steamer), which has been placed at our disposal, and landed at the pier of San Fernando a large party of officers from the ship; drove up through the town, which was all alive with negroes and coolies, men, women, and children, animals, and green decorations, to the tramway station. Up the hill thither many of the negroes and coolies ran after and alongside the carriage in which were the Governor (Henry Irving) and ourselves, and cheered us all enthusiastically and indiscriminately. One coolie woman, when unable any longer to keep up with us, fell behind most regretfully, and, prompted by the sudden impulse of offering something, took off the silver bangle she was wearing and threw it into the carriage. It made a very good ornament to a walking-stick. Another old negro, white-headed, came running with a curious knobbed stick which he had had fifty years, and wished it to be taken to England in his memory. It was so, and, 'given to the Queen,' is now stowed in the Swiss Cottage with other curiosities at Osborne.” The HMS Bacchante covered more than 40,000 miles during its voyages to the Mediterranean, West Indies, South America, South Africa, Australia, China and Japan. A trove of trinkets And when the fleet pulled into Portsmouth, England, in August 1882 (Queen Victoria was there waiting) the princes brought along tourist trinkets of the time — photographs, paintings, weaponry, jewels, some orchids in Port of Spain and bird nests from Caroni of all places. “When crossing the Caroni river noticed the mangrove-trees with their curious roots standing out from the mud, and then past a lofty tree on the left, from which dangled several orioles' nests like pouches, each more than a yard in length, and which on returning we took home with us. Walked with Mr Prestoe through the Botanical Gardens and chose some orchids to be sent to Sandringham, including one called Spirito Santo, the flower of which is exactly like a dove, and another, called the Lady's Slipper, very pretty.” But it's a curious “stick” handed to George and Albert in the town of San Fernando that is of interest here. Is it possible that the “knobbed stick” really did make it to Swiss Cottage at Osborne House 137 years ago? Was it in fact a poui wood “bois” used in the stick fight dating to the time of slavery, the ultimate symbol of resistance banned that very year? Osborne House is on the Isle of Wight, completed in 1851, and the summer home of Queen Victoria, across from Portsmouth, where the HMS Bacchante would have arrived on its return to England. On the compound is the Swiss Cottage, built for the Royal children, and the place where they would store the objects and specimens collected on their travels. No trace of gift The Brits are known for their meticulous documentation, so we check the Royal Collection Trust, which has digitised and made available much of what the royals accumulated over the years. There are literally thousands of “sticks” (what else could you give people who already had everything?) but inventory of walking sticks done in 1936 makes no mention anything from Trinidad. So we made contact with the Osborne House archivist, who agreed to check the inventory of the Museum in Swiss Cottage dating to 1904. Sorry, there were no Trinidadian sticks listed, said the curator who suggested that the use of the word “curious” in the diary entry suggests a Trinidadian-style work of art. The collection of walking sticks in the Prince Consort's Room But what about the collection of 19th century walking sticks that ended up in an umbrella rack in room used by the Queen's husband at Osborne House? Could one be the old man's stick? Nope, said the curator, it's European. Last August, the Express took a trip over to the Isle of Wight, with the intention of viewing the collection. Long story short – you can't just walk into the room and check out things. The Swiss Cottage and some part of Osborne House are open to the public. This room is not. “Of course, it's not impossible that a Trinidadian would re-present a European visitor with a European object, but it would be very unusual. Even so, there are no Trinidadian walking sticks in the collection today,” we were told by the trust. And that is where we must leave it, until someone else digs deeper and turns up something different. Source: Richard Charan, Trinidad Express April 2017 The collection of walking sticks in the Prince Consort's Room

The negative stigmas which haunt the Laventille community today do a disservice to the generations gone before since they eclipse a proud identity. La Ventille or La Ventilla (the window) is so called because of its breezy outlook perched on hills to the east of Port-of-Spain. Although now demoted to lowly use as a repeater site for the police radio units, there is a low breastwork of stone on a hill known as Fort Chacon. Hardly military in nature, being just a one-gun battery when it was erected in 1792, this was the spot from whence astronomer Don Cosmo Damien Chucurra surveyed the first accurate meridian of the new world by observing the stars in the clear night sky, as yet unobscured by light pollution. This was one of the last places where the soldiers of the island held garrison when the British, under Sir Ralph Abercrombie, seized it from Spain. More than a century after this surrender, little remained of Fort Chacon as this description shows: “The fort is hard to find, for the jungle has crept too zealously around it. It lies in the eternal shadow of green trees, while so overgrown is it with brambles that it might be a barbican of the Palace of the Sleeping Beauty. Like a secret rendezvous in a wood it is approached by a path known to few. This last stronghold of Spain, this redoubt of the dead, is a sturdy little place of grey stone, well and solemnly built. Its walls are of astounding thickness; its paved court that once echoed with the clang of arms is now a wild garden, a mere tangle of green, a court whose silence is broken only by the patter of rain and the song of birds.” In 1803 the strongman British military governor, Thomas Picton, erected another fortification in the shape of a Martello Tower (a rare piece of architecture in the Western Hemisphere). Called Picton’s Folly, the structure was a flop since its rifle loopholes in the thick walls pointed inland instead of at the coast from where any enemies were likely to originate. An attempt made in the 1820s to make Laventille a plantation district failed as Dr L A A DeVerteuil recounted in 1858: “No whites can live there; the coloured people suffer much, and Africans and Chinese are the only people who enjoy comparatively good health. It is assumed that a white man who sleeps one night on the Laventiile heights must necessarily get fever. If correctly informed, a certain number of white families from Dominica and St Lucia were induced by Sir Ralph Woodford to settle on the Laventiile hills and establish coffee estates. In less than eight years they were mowed down by fever, and coffee cultivation was abandoned.” Until a leper asylum was opened at Cocorite in 1840, Laventille was the place where those unfortunates resided, being outcasts of society. A few people of colour and suspected runaway slaves lived here in the pre-emancipation era as well. After Emancipation in 1834 the population of Laventille grew since it was close to Port-of-Spain. The city was one of the most prosperous in the West Indies. The thriving mercantile sector in Port-of-Spain required skilled and unskilled labour and this is where the newly emancipated Afro-Trinidadian found employment. The men went to work as labourers, blacksmiths, carpenters, coopers (barrel-makers), or masons while the women were employed as domestics. In the 19th and early 20th centuries Laventille was a veritable “Carrara of Trinidad.” The blue limestone of Laventille found its way into the walls of most of the prominent buildings of the period. The stone was easy to work, handsome and durable. The raw material was dug out in slabs, and carted down to the building sites where skilled stonemasons would cut and trim smaller pieces which fit together like jigsaw puzzles. A close inspection of the older edifices of Port-of-Spain would give one an idea of how solidly these stones were fitted, as many were set without mortar. Laventille limestone was used in the reclamation of the PoS harbour. The last great use of Laventille limestone was in the construction of the Churchill-Roosevelt Highway in 1942, which was the great road built by the American Army to ease transit between PoS and its base at Fort Read in Cumuto. Today, if one cares to look, the chasms of the old quarries may be seen near the top of Quarry Street. Source: Virtual Museum of T&T  Buenos Ayres is not just the capital of Argentina. It is a rural district just north of Erin in South Trinidad. It came to be simply as an amalgam of cocoa estates which in the 19th century was owned by French Creoles ( Ambard, Agostini , De Verteuil and De Montbrun) as well as smallholdings of cocoa panyols ( mixed Amerindian and Spanish) who came from Venezuela as labour for the larger estates in the period 1840-1950. Some of the old estate names survive in the village today such as La Union, La Ressource and Santa Isabella. As could be imagined the population was Catholic to a man ( there being an ancient chapel on Santa Isabella Estate which survived from 1760-1876) and spoke Spanish. In 1907 a local woman took in a few children and founded a primary school. Her hand-tinted photo is lovingly preserved in the present schoolhouse. In 1910, the Colonial Goverment built a structure which still survives as the Buenos Ayres Government School. The old building was severely damaged by a hurricane in 1933 which caused much devastation from Erin to Icacos, and was modified somewhat in the repair process. It is a quintessentially rural school, and is managed by Mr. Vallence Rambharat, a Principal who appreciates the history of the school and has wonderfully preserved its heritage. There exists in the Nat. Archives, a diary kept by a Bajan headmaster named James Rawlins who was stationed at this school in 1915. Mr. Rawlins writes" the great work of forming nascent intellects is severely hampered by the inability of the pupils to comprehend lessons in English. As I myself am a stranger to the tongue of the Spanish main, I am at a loss as to how exactly the education of the mites shall be undertaken." This photo shows the headmaster's quarters which is one of the few to survive and which was a fixture of almost every rural school. Source: Virtual Museum of T&T Trinidadians are a special people of dat there is no doubt,

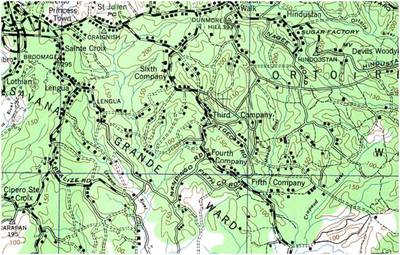

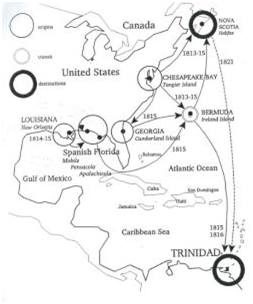

Doh care what odders say of how dey run dey mouth. But of all de special talents dat we Trinis possess, Is de way we talk dat ranks us among de best. At de street corners, in de shop or at work on any given day, Is to hear us speak and carry on in our own special way. De colourful words, de antics and de accent all combine, To create a whole language dat has stood de test of time. De way we express ourselves and de way we converse, Is truly an art of which every Trini can boast. Look at de many words dat we Trinis create, Just to make it easier for us to communicate. …Words like bobbol, skylark, commess and bobolee, Are words dat yuh cah find in any English Dictionary. Coskel, boobooloops, lahay and dingolay, Mou Mou, bazodie, jagabat and tootoolbay. So when yuh thin and frail, we say yuh maga or merasme. And when yuh fat or overweight, we say yuh obzokee. And when something small, we say chinkey instead. And we say tabanca when a woman tie up a man head. And a person who lazy, we call dem a locho. And an inquisitive person is simply a maco. Is our colourful history, yes our glorious past, Dat give us a language dat very few could surpass. So many Trinis doh speak patois again. But we use words like doux doux and langniappe all de same. So mauvais langue is when yuh bad talk people yuh doh even know. And a lighted torch we still call a flambeau. Maljo is when yuh put bad eye on everything yuh see. And when yuh shake and shiver, we call dat malkadee. And patois give us so much place names like Blanchisseusse and La Fillette. And left over food from de night before we call macafoucette. And East Indian words yuh could guess so easy. Like doolahin, beta, bap and dhoti. And we love dalporee, bodi and khumar, Baigan, barra, sahina and kuchela. Jadoo is magic dat women is use to get dey husband house and car. And if yuh talking nonsense it so easy to say gobar. And for animals and fruits look at de names we does use. De pronunciation and spelling is enough to get yuh confused. Chenette, pommecythere, pomerac and sour sop. Pewah, dongs, balata and mammy seepot. And Trini does hunt for tatoo, agouti and lappe. And instead of ants, we does say batchac. Trinis fraid macajuel, batimamselle and crapaud. And de big black vultures we call corbeaux. Trini mouth does water for crab and callaloo. Doh talk ‘bout cavindajh, pelau, pastelle and cascadoux. For seasoning shadow beni beat back all de rest. While veti-vere does make de clothes smell nice and fresh. And when we talking is like to a special rhythm dat others doh know. We have to move de whole body from we head to we toe. Watch how de hands does move as if we killing flies. And when we vex is cuya mouth or roll up de eyes. And sometimes is de mouth alone dat does all de work. Is to hear us laugh out loud when we hear a good joke. And when we laughing de mouth does open wider dan a carite. And when it come out with “Oui Foute” or “Mama Yo” it does sound real sweet. So doh laugh at we and think we antics funny. Is what we need and use to talk more effectively. But watching us talking and moving from right to left, Yuh swear is sign language to talk to de deaf. And we have a communication network dat is one of the greatest around. It beat back any newspaper, TV or computer dat dey have in town. So Maxie does tell Jane a secret story or a tory. And in two seconds Jane does run and tell she boyfriend Gary. And den Gary does tell he partners liming on de corner, So de whole ah town would know 'bout two hours later. But when de story reach back to its original source, Is never de same, it always off course. Yes, gossip does change a story from a dongs to a grapefruit just so. Where de new story come from nobody doh know. So always be careful who yuh liming with and what yuh speak, 'Cause before yuh look good all yuh business on de street. And when we start to argue is trouble in de gang, 'cause we does argue everything except de issue at hand. We Trinis does start off on one particular topic, And in no time at all we does stray from it. We does go round in circles, yes viky vi. And end up giving picong and mamaguy. But when things get heated, den de real trouble does start. Words harder dan rock stone does pass in de brew. And if yuh only take sides, yuh go get a good 'busing too. And some does use de poor ancestors to make dey attack. Dey would trace de whole family tree from yuh mudder go back. And when dat doh work, some does turn to the anatomy, Talking 'bout parts of yuh body dat dey never even see. And telling stories is a special talent we got. Trinis could make up a story right dere on de spot. Listen to a husband when he reach home late, He would never say dat wid de outside woman he had a date. He go tell his wife 'bout parang or late night class. How he working overtime and de car run out of gas. And when de cocaine disappear from de police station without a trace. It easy to blame de greedy rats and done de case. And dats why we does have Commission of Enquiry every odder day. So each one could tell de same story in a different way. But when it come to stories, politicians are de very best. Promising brighter days and a better life and nothing less. Yes, Trinis smart and it is little wonder den. Dat up de islands dey does say “Trickydadian.” So talk for we Trinis is a way of life. Is how we assume ourselves and deal wid strife. Listen to de sweet talk of a true Trini male, Dat could win de heart of any Trini female. And every spectator does turn a coach at a cricket or football match. Shouting out advice for bad play or dropping a catch. Man we know how to talk before we could creep. We could out talk all odders in one clean sweep. A Trini who cah talk will laugh instead. And if he cah do dat, he better off dead. source: Chin Up  I bought a book today titled to the point - "Towns and Villages of Trinidad and Tobago" by Michael Anthony. There are approximately fifty towns described in it, each one dedicated seven pages to a geographical and brief historical summary. It's a decent book, written for the layman but containing adequate information to satisfy a "local" knowledge craving. For the sake of sharing this information, I thought I'd list one fact (usually the origin of the name) for most of the towns described in the book: 1. ARIMA is the Amerindian word for "water". It was so named as the village was built around a river. 2. AROUCA is based around the word "Arauca", which is the true name for the so-called Arawak. 3. The adjacent beach, BALANDRA, is named after a type of boat that docked there. 4. BARATARIA is possibly named after a prank involving a fake island of the same name in Cervantes' Don Quixote. "Barato" itself means cheap. 5. BICHE is named after the French word for "beast" because it was first started off as a settlement for hunters. 6. The settlement was first called Ladies River, but later on a French surveyor named it after the French term for "washer-woman" -BLANCHISSEUSE. 7. When boats were docked in Port-of-Spain, they were carried along the bay to be cleaned. This was called "careening" and so sprang the nameCARENAGE. 8. CAURA was based off of an Amerindian word "Cuara" which meaning is lost now. The settlers of Caura were said to be so lazy and secluded that their village never thrived and was left mostly abandoned. A CORRECTION MADE BY A DESCENDANT FROM THE CAURA AREA: Caura ancestors were not lazy. They carried their church brick by brick to the Lopinot Valley. A dam scheduled there was never built and the Government never gave them back their land. 9. When the Spanish sailors arrived at this coast, they noticed many tall cedar trees. And they called it the Spanish word for cedars, CEDROS. 10. CHAGUANAS is named after the group of indigenous peoples that lived there, known as the Chaguanes. Smaller villages in Chaguanas were so named to positively motivate its early settlers - Felicity, Endeavour, Enterprise. 11. COUVA was a corruption of Cuba, due to the tendency to pronounce "B" as "V" in the Spanish language. 12. CUNUPIA is named after the Spanish word "conupia", which when translated means "canopy". 13. DIEGO MARTIN is simply named after the Spaniard who discovered it, Don Diego Martin. 14. FIFTH COMPANY VILLAGE is so named after the temporary settlement of the 5th company batch of black American soldiers who stayed here during the war of 1812. 15. The villagers were very pleased when a man named Clifton Flanagin came and built a successful railway system, and thus changed the name of their village to FLANAGIN TOWN. 16. The indentured labourers from Uttar Pradesh named FYZABAD after a province they lived next to, known as Faizabad. 17. The first spot sighted by Columbus. This spot may also be known as GALEOTA POINT, which means "galley", as Columbus believed it to look like a galley under sail. 18. GUAYAGUAYARE was named after the indigenous mocking the sounds of the sea at that point. 19. An icaco shrub, more commonly known as "fat pork", provided the inspiration for the name, ICACOS. 20. When Sir Walter Raleigh patched his ship up with the pitch from the Pitch Lake, he gave the village the name LA BREA, which simply means "The Pitch". 21. LAVENTILLE is a corruption of "La Ventaille" (or The Vent), so named for the passage of the northeast trade winds through this area. 22. A new incoming Governor by the name of James Longden was determined to leave his mark on this country and so had a town named after him, called LONGDENVILLE. 23. In the 1700's, a young man from Louisiana travelled to Santo Domingo. When war involving Touissant Louverture broke out, he sneaked into a ship, which then carried him to Trinidad. He settled in a spot there after being granted a parcel of land for cocoa. The man's name was Charles Joseph Count de LOPINOT. 24. Along the coast there are tiny fruits known as manchineels. They are small and poisonous and look like tiny apples. The village near this coast was given the Spanish word for "little apple", which is MANZANILLA. 25. When the Spanish visited here, they came for the seaside view. It was described as "Mar Bella", or ‘beautiful sea', which was later turned to MARABELLA. 26. MARACAS was so named after the musical instrument, which we sometimes call the "chac-chac". 27. MATURA is the Spanish word for "high woods", named by the surveyors visiting there. 28. The maya plant grew prolifically in MAYARO. The word "ro" in the Amerindian language meant "the place of", so Mayaro denotes "the place of the maya plant". 29. A place renowned for having spirits, MORUGA was named after a river lined with abandoned fishing settlements, with many of the villagers claiming that an apparition dwelled in the waters. 30. NAPARIMA is named from the Amerindian word "Anaparima", which means "single hill". 31. Due to the nearby presence of the Oropouche Lagoon and rice paddies, the dwellers took to calling the village "pengyal", which in Tamil means "swampy area". This was later renamed PENAL. 32. POINTE-A-PIERRE was only so named because of its French settlers - Pierre being a popular French name. Courtesy of http://jus-trini-tings.tumblr.com  The Merikins were African-American refugees of the War of 1812 – freed black slaves who fought for the British against the USA in the Corps of Colonial Marines and then, after post-war service in Bermuda, were established as a community in the south of Trinidad in 1815–16. They were settled in an area populated by French-speaking Catholics and retained cohesion as an English-speaking, Baptist community. It is sometimes said that the term "Merikins" derived from the local patois, but as many Americans have long been in the habit of dropping the initial 'A' it seems more likely that the new settlers brought that pronunciation with them from the United States. Some of the Company villages and land grants established back then still exist in Trinidad today. During the American Revolution, freed black slaves were recruited by the British. After that war, they were settled in colonies of British Empire including Canada, Jamaica and the Bahamas. During the War of 1812, there was a similar policy and six companies of freed black slaves were recruited into a Corps of Colonial Marines along the Atlantic coast, from Chesapeake Bay to Georgia. Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, on taking over the command of British forces on the North America station on 2 April 1814, issued a proclamation offering a choice of enlistment or resettlement Unlike the American refugees who were brought to Trinidad in 1815 in ships of the Royal Navy, HMS Carron and HMS Levant, the ex-marines were brought there in 1816 in hired transports, Mary & Dorothy and Lord Eldon. There were 574 former soldiers plus about 200 women and children.To balance the sexes, more black women were subsequently recruited – women who had been freed from other places such as captured French slave ships. The six companies were each settled in a separate village under the command of a corporal or sergeant, who maintained a military style of discipline.The villages were named after the companies and the Fifth and Sixth Company villages still retain those names. The villages were in a forested area of the Naparima Plain near a former Spanish mission, La Misión de Savana Grande.[Each soldier was granted 16 acres of land and some of these plots are still farmed today by descendants of an original settler.The land was fertile but the conditions were primitive initially as the land had to be cleared and the lack of roads was an especial problem. Some of the settlers were craftsmen more used to an urban environment and, as they had been expecting better, they were disgruntled and some returned to America. The rest persisted, building houses from the felled timber, and planting crops of bananas, cassava, maize and potatoes. Rice was introduced from America and was especially useful because it could be stored for long periods without spoiling. Twenty years after the initial establishment, the then governor Lord Harris supported improvements to the infrastructure of the settlements and arranged for the settlers to get deeds to their lands, so confirming their property rights as originally stated on arrival. As they prospered, they became a significant element in Trinidad's economy.Their agriculture advanced from subsistence farming to include cash crops of cocoa and sugar cane. Later, oil was discovered and then some descendants were able to lease their lands for the mineral rights.Others continued as independent market traders. Religion Many of the original settlers were Baptists from evangelical sects common in places such as Georgia and Virginia. The settlers kept this religion, which was reinforced by missionary work by Baptists from London who helped organise the construction of churches in the 1840s.The villages had pastors and other religious elders as authority figures and there was a rigorous moral code of abstinence and the puritan work ethic. African traditions were influential too and these included the gayap system of communal help, herbal medicine and Obeah – folk magic and witchcraft. A prominent elder in the 20th century was "Papa Neezer" – Samuel Ebenezer Elliot (1901–1969)– who was a descendant of an original settler, George Elliot, and renowned for his ability to heal and cast out evil spirits. His syncretic form of religion included veneration of Shango, prophecies from the "Obee seed" and revelation from the Psalms. The Spiritual Baptist faith is a legacy of the Merikin community. Sources credits

Research complied Jalaludin Khan 2017 Text Merikins Wikipedia The Merikens: Free Black American Settlers in Trinidad – John McNish Weiss Photos The Merikens: Free Black American Settlers in Trinidad – John McNish Weiss Sources further readings Benn, Carl . Essential Histories: The War of 1812. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002. Brereton, Bridget . A History of Modern Trinidad 1783-1962. Champs-Fleurs: Terra Verde Resource Centre, 2009. Governor Sir Ralph Woodford to Colonial Secretary Earl Bathurst 28th August 1816. Trinidad Duplicate Governor’s Dispatches January 7th 1815 to December 7th 1816. McNish Weiss, John . The Merikens: Free Black American Settlers in Trinidad 1815-1816. London: McNish and Weiss, 2002. Williams, Eric. History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago. London: Andre Deutsch, 1964. Winer, Lise . Dictionary of the English\Creole of Trinidad and Tobago. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2008. Wood, Donald . Trinidad in Transition: The Years after Slavery. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987. Gerald Horne, Negro Comrades of the Crown, African Americans and the British Empire Fight the United States Before Emancipation (New York: New York University Press, 2012); Gene Smith, The Slaves Gamble, Choosing Sides in the War of 1812 (New York: St Martin’s Press, 2013; John Weiss, “The Corps of Colonial Marines: Black Freedom Fighters of the War of 1812,” http://www.mcnishandweiss.co.uk/JWhistoryindex.html; The Merikins: Free Black Settlers 1815-1816, Trinidad and Tobago’s National Library and Information System Authority http://www.nalis.gov.tt/…/TheMeriki…/tabid/563/Default.aspx…  Unlike today where detainees of the state are kept housed and fattened because taxpayers have nothing else to do with their money, in the prison system of yesteryear, these scapegraces were made to EARN THEIR KEEP. On the dreaded island prison of Carerra , inmates were ferried across to nearby Kronstadt island to pulverize chunks of limestone which would be used in the Public Works Department for road repairs. Since this was not possible at the Royal Jail on Frederick St. (constructed in 1812) prisoners were formed into chain gangs and marched out every morning to undertake public works around POS. This was mainly an initiative of the clever Capt. Percy Fraser who was the Superintendent of Prisons from the late 1890s well into the 1930s. Chain gangs from Royal Jail had previously been used to maintain Lapeyrouse Cemetery as early as 1840, but Capt. Fraser extended their scope to include clipping of road verges, cleaning of canals and removal of dead animals. This of course was not only meant to make prisoners earn their keep, but also eased the burden on the coffers of the continually cash-strapped POS City Council which was forever in a deficit . Sadly, chain gangs are no more since it has been seen as more feasible to give prisoners an extended holiday courtesy the public purse. This photo from 1926 shows a chain gang around Belmont Circular Road being slow-marched while an armed officer (in helmet) follows them. The car also would be part of the procession, most likely carrying other armed personnel. Source: Virtual Museum of T&T  Image of the Speyside coastline, one of the priority areas identified by the Inter-American Bank for coastal erosion. Trinidad is shrinking and changing as it becomes increasingly vulnerable to storms, flooding and other natural disasters which cause coastal erosion and the retreating of the shoreline. In Columbus Bay, in West Trinidad, the coastline has retreated by 150 metres since 1994, losing 6.5 hectares of land. In the western part of Guayaguayare, the shoreline retreats annually by approximately one metre per year.

In Cocoa Bay, north of Manzanilla, the retreat is slightly more accelerated at 1.45 metres annually. “The country is shrinking in some parts but it might be expanding in others, but the number of areas where it is shrinking is a lot more than the areas where it is expanding,” said Michele Lemay, Integrated Coastal Zone Management Specialist at the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB). Lemay has spent much of the past two decades in the region, doing research on coastal erosion and providing expertise on the subject. In an interview at the IDB office in Port-of-Spain, Lemay said at a national level, in the last decade, from 2005 to 2015, there had been a five-fold increase in Trinidad of storm events, erosion and flooding when compared to the decade prior. She said this also coincided with an increase in coastal erosion. “T&T is becoming more vulnerable and when you think about the cost of this in terms of getting to work, taking kids to school, damages to property and household, you see the more obvious effects,” she said. “It happened in Matelot and Grand Riviere, before that it happened in Manzanilla and Mayaro. We found that the frequency of erosion and flooding in the coastal zone has increased considerably, even in Tobago. “Sea level rise is going to worsen things and speed it up but we do know that up to the year 2100 there is a potential of 1 metre increase for sea level rise but I think in T&T there is more research needed to bring down the global models and come up with local numbers.” Lemay said the Caribbean was more vulnerable than other places because countries are on the hurricane track or have more frequent storms. “Caribbean islands are very densely populated so there are a lot of infrastructure along the coast. The more you build your shoreline, the more you create circumstances where you can have coastal erosion.” She said the IADB had made recommendations for government to focus on priority areas for mitigating measures. The areas identified were Speyside in Tobago, Mayaro, Guayaguayare area, Cocos Bay and San Souci as they are worse affected in the sense that when events happen, flooding or erosion they affect communities which are isolated. “The idea is to promote people to stay at least 50 metres away from the shoreline for construction. Sometimes you have private ownership of land right up to the beach. You can tell people, this is your private property but do not build hard structures too close to the ocean.” Lemay said T&T already had an advantage over other countries in the region in terms of research from the Institute of Marine Affairs (IMA) and installation of a Coastal Protection Unit under the Ministry of Works in 2014. “What is needed is much closer monitoring of the shoreline. You can measure how it retreats, in some cases it moves forward or becomes more steep which is a clear sign of erosion. “Our shorelines in the Caribbean are very vulnerable to storm events, flooding and erosion and traditionally the solution has been to build emergency structures when houses start losing their land and things like that. An integrated approach combines technically advanced solutions with regulatory measures and science. “The work of the IMA and coastal protection unit is going in that direction.” She said other measures needed to take place such as involving residents of affected communities in solutions like planting mangroves across the shore. Source: Trinidad Guardian, Aril 16, 2017 |

T&T news blogThe intent of this blog is to bring some news from home and other fun items. If you enjoy what you read, please leave us a comment.. Archives

July 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed